Welcome to the second of my write-ups of the books about the 2024 general election. This time it is Lord Michael Ashcroft’s Losing it: the Conservative Party and the 2024 general election.

To get future reviews direct to your inbox too, sign up here if you are not already subscribed to this free newsletter:

Losing it by Michael Ashcroft

The first book I reviewed, Anushka Asthana’s Taken As Red, and this one from Lord Ashcroft are both similar and very different.

They are similar in that both have, in book publishing terms, come out very quickly after the general election, and have done so by focusing on one particular way of telling the election story, a way that is suitable for such quick turnarounds.

But while Asthana’s book used a Westminster-focused journalistic narrative style to achieve that, Ashcroft’s has come out so quickly by being simply the write-up of some prompt polling and focus groups.

Both books therefore consider only one way of looking at the election and so if you find one of interest, you almost certainly should also reach for the other to get a different angle. Other books to come will take more in-depth (and slower) approaches, or mixes of approach. But they are not yet out.

For all the narrowness of Ashcroft’s approach, using just his own polling and focus groups from the immediate run-in to and aftermath of the election, it is an approach that has served us some very good analysis after previous elections. His series of such post-election books has always been on my ‘must read’ list since the first came out after the 2005 general election.

The inclusion of focus group conclusions also helps bring to life the way in which the public really sees politics and elections. As I wrote about his 2015 volume:

In the focus group held the day before the 2015 Budget, none of the participants knew the Budget was due the next day, yet they were able to make pretty coherent judgements about different parties and their leaders. That mix of ignorance and sense is at the heart of how politics really works – not the details that usually fill up political coverage.

Of course, the use of focus groups means that - even more than with opinion polling - we have to trust that the author or pollster is accurately presenting the evidence. Given Lord Ashcroft’s controversies and his very clear Conservative Party allegiance,1 that may give some pause for concern with this book. All the more so given the controversies over some of his non-polling books.

But, as with his previous election polling books,2 he is very happy to explicitly lay into his own party where he feels it is merited.3 Of the 2024 Conservative effort he says:

The Conservative administration became, to use a technical term from political science, a total shambles. The Tories didn’t so much play a difficult hand badly as drop all their cards on the floor…

Reminding the Republicans that they had to deliver for their voters, Ronald Reagan used to like to say, ‘you’ve got to dance with the one that brung ya’. But if you will permit another metaphor, it’s not as if the Conservatives took one group of voters to the party and then danced with another. It’s more that they went straight to the bar, got in a fight with their mates, tripped over their own feet and passed out in the car park. In the rain.

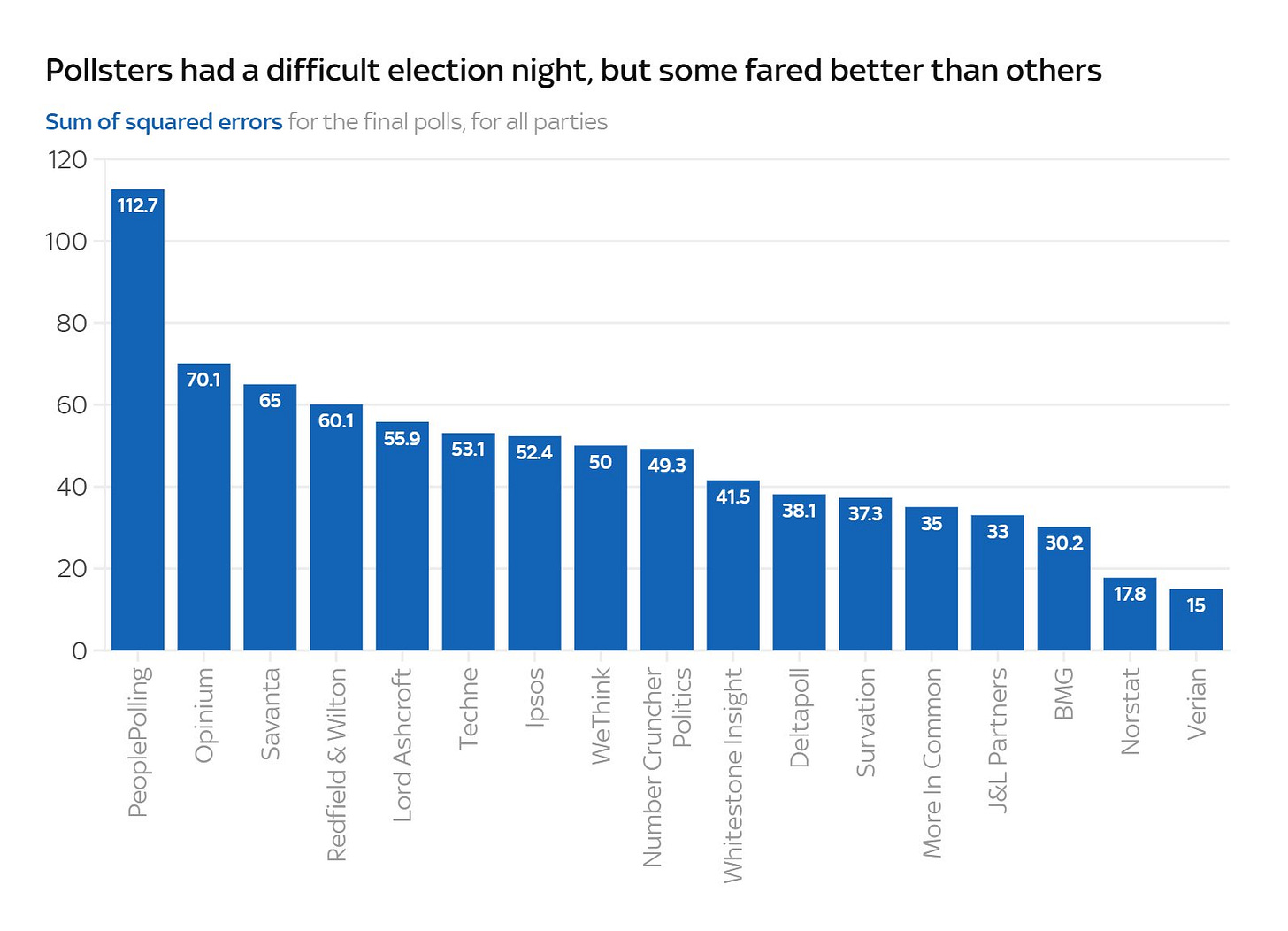

As for the accuracy of his polling, the analysis by Will Jennings shows that his final pre-election poll was okay, though not brilliant. His final figures were (with the result in brackets) Labour 38% (35%), Conservative 19% (24%), Reform 18% (15%), Lib Dem 11% (13%) and Green 8% (7%). That put his poll not near the top of the table, but only slightly worse than, for example, respected pollster Ipsos and a good notch better than Opinium with its much talked about methodology:

So while there should be some caution applied to any story told based on just the one pollster,4 the track record of the Ashcroft polling is good enough for the book to be worth a read.

What then do we discover when reading it? The main argument of the book is that the Conservative defeat was not about policies or about being too much or too little right wing. Rather it was about character:

Our participants [in focus groups of people who voted Conservative in 2019] complained at length about failure to control immigration, the cost of living, housing, the economy, the state of public services, and much more. But when we asked them to complete the sentence, ‘By 2024 the Conservative Party had become too…’, the answers were more often about character than politics. ‘Broken’, ‘chaotic’, ‘clueless’, ‘complacent’, ‘confused’, ‘corrupt’, and ‘crooked’ only take us to the third letter of the alphabet … and don’t forget, these are all from people who voted Tory in 2019.

Ashcroft goes on to point out that 49% of even 2024 Conservative voters thought the party deserved to lose.

Partygate and the PPE scandals, followed by Liz Truss were hugely damaging, according to his data. (Though the mention of PPE scandals as being a big drag on the Conservative vote was for me another reminder of the risk of reading too much into any one pollster’s figures. It is giving away no secret internal Lib Dem data to point out that the party’s very successful Parliamentary by-election literature in the last Parliament barely mentioned the topic. That gives a clue about what other data might have been suggesting.)5

One of the advantages of Ashcroft’s use of focus group findings, with extensive quotes from participants, is it also helps highlight what really cut through to voters, including in this case the line about Rishi Sunak being richer than the King.

Added to these problems for the Conservatives, three of the major props for the Conservative 2019 win were gone by 2024 - Boris Johnson, Jeremy Corbyn and a looming Brexit deadline. Ashcroft’s 2019 volume also pointed to a wider problem in Labour’s perception in the public’s eyes beyond even Corbyn and Brexit. It is more debatable how far that was fixed, but as 2024 showed, Labour’s overall standing was certainly significantly improved under Keir Starmer.

One of the issues likely to be of continuing debate is what role immigration played in the Conservative defeat, and whether the party was wise to focus so much on the issue (and whether it should continue to do so). The implications of Ashcroft’s polling is that the Conservative problem on immigration was one of competence rather than the issue itself. That is, the government chose to talk up an issue that it then failed to deliver on, and it was that failure of competence which cost them support. It was mostly talking of an issue being important and then failing on it on their own terms that mattered, and not so much the issue itself.

As the focus groups of Conservative defectors (voting for the party in 2019 but not in 2024) found:

We asked [people] to complete the sentence, ‘By 2024 the Conservative Party had become too…’ Nearly all the responses related to character and competence rather than political direction.

The text is on occasion a slightly laborious retelling of what is in the immediately adjacent graphs (generous in number and helpfully in colour). The two also are not fully in synch on a few occasions.

But these sort of issues do not make the book one to avoid. Rather it is one to pour over, especially as it is full of little details that can spark much thought.

One example is the polling about whether people thought each party was clear what it stood for. ‘We must be clearer what we stand for’ is a common refrain from any party that is struggling. And yet… while the Conservatives came fourth out of themselves, Labour, Reform and the Lib Dems with only 15% agreeing it was clear what they stood for, the party that came out top by some margin - Reform with 35% - finished in the election 20 percentage points and 407 seats behind Labour, who scored lower than them with 28%. The Lib Dems, winners of 72 seats to Reform’s 5, were also behind Reform, on 20%. Which suggests those calling for greater clarity over what their party stands for may be frequently misdiagnosing their party’s situation.

Or for another snippet, enjoy the fact that Reform voters are those least likely to think that the internet is a force for good.

And finally, the Pack Mentions Index (PMI) score for this book is a healthy zero, helped by the fact that the book focuses so tightly on polling and focus groups. Wisely, the public had better things to do than remember that I was briefly an interim co-leader of a party during the last Parliament.6

Get the book

You can get your own copy of Michael Ashcroft’s Losing it: the Conservative Party and the 2024 General Election:

Bookshop.org (“an online bookshop with a mission to financially support local, independent bookshops”)

The next book

My plan is for the next book to be Tim Ross and Rachel Wearmouth’s Landslide: The Inside Story of the 2024 Election which is due out in late November. I hope therefore to get my review out by the end of the year.

But you can zip ahead of me by getting your copy to read as soon as it comes out:

The previous book

Anushka Asthana’s Taken As Red: How Labour Won Big and the Tories Crashed the Party.

Links to books are affiliate links which generate a small commission for each sale.

Although he once flirted with becoming a Liberal Democrat.

For convenience, from here on I am using ‘polling’ as shorthand for ‘opinion polls and focus groups’.

And of course I hope you do not totally discount polling discussions from active supporters of a political party given I fit that bill too…

Particularly given, for example, the very different age profiles for the Liberal Democrat vote at the 2024 general election depending on the pollster you pick. You can claim that the Lib Dem vote share went up the older voters were, that it went down the older voters were or that it was unaffected by age. In all cases you can point to a reputable public poll to back up your claim.

Another difference between Ashcroft data and that of others is over the placement of Reform voters on the political spectrum. Ashcroft’s data has them to the right of the Conservatives while Paula Surridge’s analysis puts them to the left.

Though I would have loved to see the facial reaction of the focus group moderator if this had come up.