Taken As Red: Anushka Asthana

Welcome to the first of my write-ups of the books about the 2024 general election. The debut book is, appropriately enough, the first one to be published: Anushka Asthana’s Taken As Red: How Labour Won Big and the Tories Crashed the Party.

To get future reviews direct to your inbox too, sign up here if you are not already subscribed to this free newsletter:

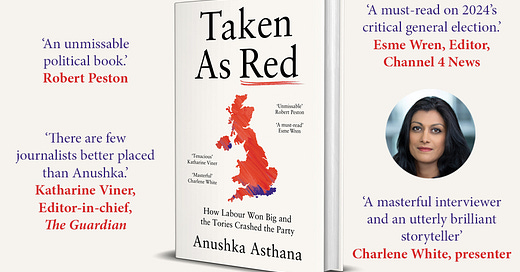

Taken As Red: How Labour Won Big and the Tories Crashed the Party

Let us start with the book’s cover. The map of the UK1 on it uses just two colours, Labour red and Conservative blue, and while the blurb on the cover mentions a third party, Reform, that is it. The book does give some attention to others, including the Liberal Democrats and Greens, but the cover sets the tone. This is a book mostly about Labour, with a major supporting role for the Conservatives, and Reform being the preferred pick for anyone else getting in a look-in during the text.

That Labour focus comes through in the richer accounts given to Labour’s campaign and personalities than those for people from other parties. For example, Robert Jenrick’s transformation from close ally of Rishi Sunak and seen as a (relative) centrist in the Conservative Party, appointed to the Home Office by Sunak as a safe pair of hands in order to keep tabs on a more right wing Home Secretary, into instead a strident critic of Sunak with a much more right wing approach to immigration gets just the briefest of mentions. Two short sentences is all we get, drawing on no sources or evidence and leaving open whether it was a genuine or cynical change of heart by him.

By contrast, even those familiar with Labour figures have praised the accounts of Morgan McSweeney’s rise in Labour, while the detailed analysis of Keir Starmer’s leadership paints a convincing picture of someone who, far from being the uber-cautious carrier of a Ming Vase of popular punditry portrayal, comes through as a coldly ruthless person. Also personally very kind and supportive of colleagues, yet ruthless in his willingness to get rid of them.

Where the controversies over someone can be fairly covered by drawing on competing Labour sources, such as over Starmer’s personality, then the book tells the story very well. The Morgan McSweeney accounts show the strengths and limitations of that approach. The strength is the pacey but detailed story of his earlier days in Labour and the experiences that shaped his approach to winning a general election. The limitation is that the account seems to draw wholly on Labour sources. Therefore, McSweeney’s role in the 2006 Lambeth council elections is all one of praise for his organisational abilities. Left out of the story are the highly negative personal smears that appeared in Labour’s leaflets in that campaign.

Does he still revel in such tactics? (Which might help explain some of Labour’s attacks on Rishi Sunak.) Or has he since repudiated such campaigning? Or perhaps the smears happened despite his internal protests at the time, or outside of his control? Those questions are neither asked nor answered.

But for that omission, there is much else that is very good in the book. Even apparently baffling blunders like Rishi Sunak skipping key parts of the D-Day commemorations make more sense to me after reading the book (with its account of Sunak’s history of disliking travel and trips away). Likewise, the accounts of Keir Starmer’s early turn towards scepticism over freedom of movement illuminate much of his subsequent soft pedalling on Britain’s future relations with the EU.

Occasionally, the book’s explanations do not really convince. Did the Conservatives really rule out a general election on local election polling day in May just to help out a couple of their Mayors? Was Sunak really so dedicated to the electoral success of Conservative Mayors that their electoral interests had a veto over his plans for his own survival? That seems unlikely. Though to be fair perhaps the book does not provide a convincing explanation because the decision making was so poor that there is not one. And overall, the book definitely leaves you understanding more by the end than when you started.

The book is also very entertaining, including the particularly brutal line that rounds off chapter 9: “But at least the [Conservative] party retained its reputation for economic competence”. Brutal because chapter 10 is simply titled, “Liz”.

There is plenty of good colour too on topics such as just how unprepared the Conservatives were at the constituency level for the general election. Though again the explanation on why this was all so shambolic seems unconvincing. The Prime Minister was meant to be the king of spreadsheets, if anything spending too much time getting drawn into details. Yet basics such as ‘will our candidates be in the UK and able to start campaigning?’ were - along with an umbrella - missing from the plans for the election to be called. The book gives us one dismissive quote from a Sunak team source that MPs should have been ready, which does not satisfy as an explanation for a blunder which was on a par with a railway company launching a new timetable without having its drivers in place.

There is also a heavy smattering of quotes from genuinely expert political scientists. So although the book’s quick turnaround means it is light on data and number crunching, you do get a strong sense of what the data experts currently think.2 Therefore the lightness of the approach to data is only really an issue over the account of the Conservative Party’s decision to put immigration at the heart of its campaign. The book gives a good account of the personalities and narrative around the decision, but it is not the place to turn to for a detailed exposition of the evidence for and against the effectiveness of this decision.

This sort of instant reportage election book - heavy on personal colour from the author’s sources, light on analysis and data - has its place. Compared to similar books from previous elections, such as Nicholas Jones’s from 2010 or Jon Smith’s from 2005, Taken as Red has a strong claim to be the best of that class of election book. I certainly expect to be picking it up to re-read sections in future.

I suspect, as with Nicholas Jones’s 2010 volume, the Lib Dem result (into government in 2010, best result for a century in 2024) made the party a larger part of the book than originally planned. As a result, the Lib Dem content is relatively thin and seems to draw on only a small number of sources.

But what is there is sharp, accurately delving into who really formed Ed Davey’s inner team, even if the account does make it sound like Kath Pinnock was chair of the party’s election committee since the 2019 election - cutting out of the story the important role of Lisa Smart who chaired the committee for much of the last Parliament. Plus Ed Davey’s chief of staff, Rhiannon Leaman gets her name consistently misspelt. Even so, it is to the book’s credit that she is mentioned multiple times. I suspect a fair number of even very active Lib Dems will learn something from the book about their own party’s campaign.

And finally: the book has one mention of me. Which for such books, I view as being the perfect score. One mention shows that the author has escaped at least a decent distance from the insider Parliamentary bubble to get as far as knowing about more. More than one mention though, well who would want that?

Get the book

You can get your own copy of Anushka Asthana’s Taken As Red: How Labour Won Big and the Tories Crashed the Party from:

Amazon (includes audio book version)

Bookshop.org (“an online bookshop with a mission to financially support local, independent bookshops”)

Next up

My plan is for the next book in a couple of weeks or so is to be Michael Ashcroft’s Losing it: The Conservative Party and the 2024 General Election. You can zip ahead of me by getting your copy here:

Links to books are affiliate links which generate a small commission for each sale.

The UK minus Orkney and Shetland, that is.

What they think may change as the authoritative data from the British Election Study is released and starts to be used in analysis. But while the BES data comes out quickly judged by academic timescales, it is too slow for a quick turnaround election book.

I still wince at the absence of an apostrophe.